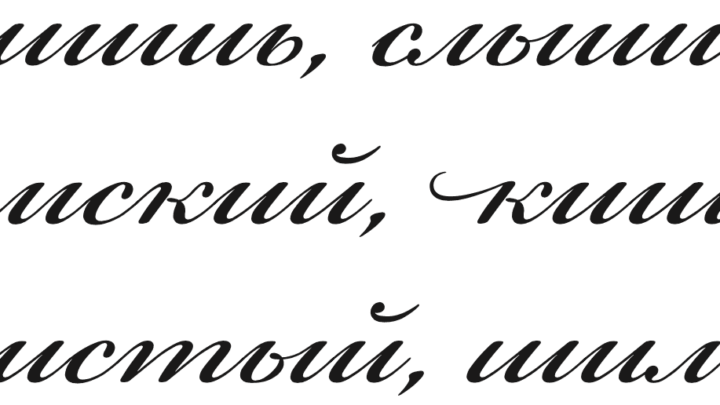

Russian and English have several deceptive “false friends.”

About 10% of Russian words resemble their English counterparts. But don’t get too comfortable with guessing. These are also many words that look or sound the same but have different meanings between the two languages. For example, in English, “angina” means chest pain. But the Russian word Ангина means tonsillitis, a much less severe affliction…